|

Late last week, I attended a downtown managers' conference where, though it was not on the agenda, a great deal of the discussion centered around the impact of the Corona Virus. Downtown managers were anxious about how to provide leadership and help to small businesses in their jurisdiction. With social distancing requirements in place and mandatory restaurant and bar closures in many parts of the country, downtown businesses will be struggling to survive a slow down in business with no end in sight.

The usual methods used by downtown place management organizations such as Main Streets, downtown development authorities, and business improvement districts involve attracting large volumes of people. Oftentimes, when downtown business needs a boost, the downtown organization creates an event to attract more potential shoppers and diners. This is not an option in the age of COVID-19. Even simply advertising for downtown is extremely complicated by the need to keep people apart. So what can downtown managers do? They should be looking at both short-term and long-term strategies to navigate this crisis. Here are three things downtown organizations can do in the short term:

For the long term, its important that downtowns, as well as larger municipalities, have a renewed focus on resilient economic development. One thing that can be done now is developing an Economic Development Strategy now so that your downtown can hit the ground running when things get back to normal. This kind of strategy should include a clear vision for your downtown's future, targeted strategies to achieve it, and the means to measure progress on achieving the vision. These are trying times requiring collective financial pain. Downtowns can get through it by focusing on helping their small businesses now, and laying a path for a successful future.

1 Comment

Last year, U.S. News and World Report ranked states by housing affordability. They compared the cost of living with how much citizens in each state had to spend. According to their ranking, Ohio was the most affordable, with Hawaii being the least. Ohio ranked highest even though it has only the 11th lowest cost of living. What made Ohio rise to the top was how their household income favorably compared with cost of living. Mississippi, on the other hand, which has the lowest cost of living in the 50 states, ranks 13th in housing affordability thanks to its lower incomes.

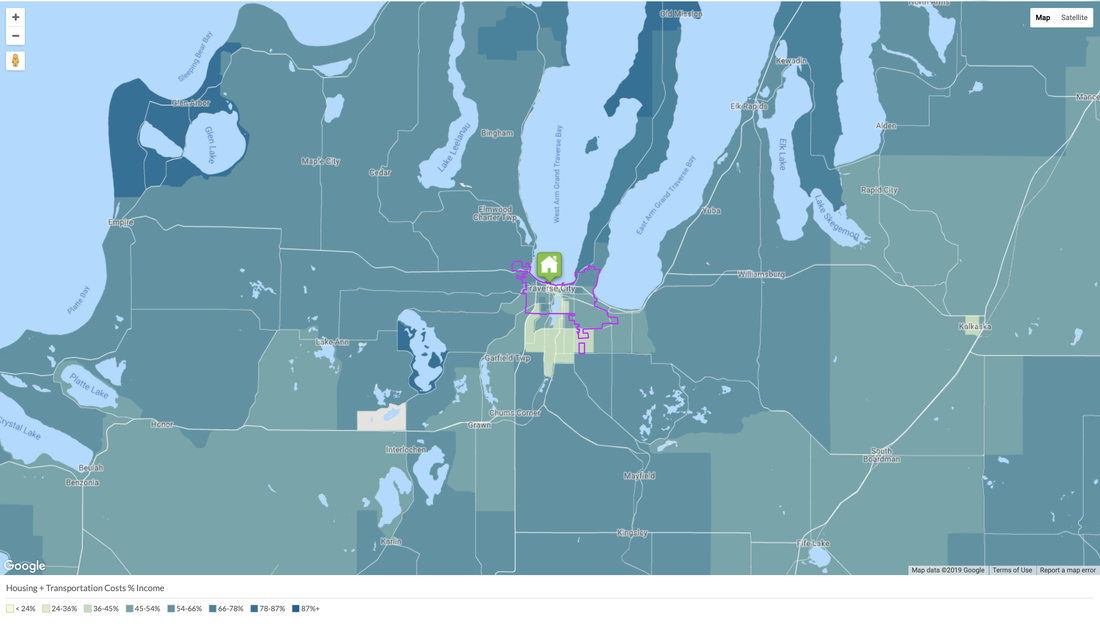

Housing costs typically consume the largest portion of a household budget. The category usually in the number two spot is transportation. When an individual or family is making a decision on where to the live, they often overlook how transportation costs can add a significant amount to their household spending. Homes may be cheaper away from town, but did you consider how much more you might spend traveling to work, shopping and other trips? To help draw attention to transportation cost the Center for Neighborhood Technology created a Housing and Transportation Affordability Index (H+T Index). This index compares housing prices with incomes, but also adds in transportation costs. They regard 45% as the most a household should spend on housing and transportation. Their online tool is available to all at https://htaindex.cnt.org. You can see down to the neighborhood how well home prices match up with incomes. Then you can add in transportation costs and see how affordability shifts. Where I live in Traverse City, Michigan, in town houses fetch nearly twice the cost per foot as those in the suburbs, and even more than twice those out of town. So a home buyer would naturally be inclined to look to the ‘burbs and beyond for value. But according to the H+T Index, most in town neighborhoods are rated affordable, whereas most neighborhoods beyond are not. And affordability generally fizzles the further away from town you get. Now some of this has to do with higher income households being attracted to urban living, but the impact of transportation costs is unmistakable. Living in town affords households to shed a car, or even two, and can lessen the impact on the car or cars they do own because they are used less. The ability to walk or bike to destinations, along with the availability of fixed route transit, and on call services like taxis and Uber, make personal cars costs go down (or disappear!) The Center for Neighborhood Technology calls this “locational efficiency.” Living in a location efficient neighborhood can save you $10,000 annually, or more. Consider that the next time you are looking to move.  When it comes to downtowns, we often get what we ask for…or what we don’t. We focus on place-making, great events, on improving retail, attracting office businesses and having a good mix of housing, all inside the boundaries of our downtown. But what happens outside of its boundaries is just as important, and has a profound impact on the success or failure of your town. This is especially true of smaller towns. It is critical to be aware of what is happening outside your borders, and to advocate on your downtown’s behalf. When downtown managers are struggling to understand where their downtown is and what it needs, often I recommend a market study. These studies looks at real estate in your district and measure such factors as vacancy rates, retail leakage and turnover. Market studies also look at your downtown’s trade area. A retail trade area is the geography that your shops and restaurants pull customers from. The extent of a trade area depends on what kind of pull factor your town exudes, and also on travel time for the shopper. The more compelling a downtown you have, the more pull factor it has, and the further diners and shoppers are willing to travel to go there. This, of course, it why downtown organizations work tirelessly on improving their town’s draw and appeal. Besides identifying the geography of the trade area, market studies look at the buying power within in. Your downtown may enjoy spending from daytime workers, but for smaller towns without a significant office base, the bulk of spending comes from households in and around your town center. Buying power is a function of the average household income in your area and the number of households within your trade area. The more households, the better. But is your town spreading out beyond your downtown’s trade area? This is a slippery slope you do not want to slide down. Small downtowns with 40 or less shops can have a trade areas of only three miles. If a town’s trade area is only three miles but is seeing housing growth beyond three miles, it likely is losing potential spending. When housing spreads out, so does retail, and usually in the form of auto-centric sprawl retail. This further hurts downtowns by creating retail competition that draws more spending dollars away from within that downtown’s trade area. The slippery slope of this phenomenon includes overbuilding retail, which ultimately hurts everyone. As homes and retail spread further out, so do other uses like office, services, industrial and other uses exacerbating the problem. There was a time in Traverse City when our well-meaning Chamber of Commerce was promoting the idea of a suburban office park. The Chamber felt such a park was needed to help attract businesses that bring with it the kind of jobs Traverse City needed. The Downtown Development director at the time, the iconic Bryan Crough, argued against such a park. He knew that this park would draw away many of the office businesses already located in downtown. Bryan’s message was “Downtown is our office park!” Bryan prevailed and the suburban park was never build. Instead, downtown became the strongest and highest value office submarket in the region. We often feel that as downtown managers we do not have control of what happens beyond our borders. We may not, but we have influence, and that influence should be brought to bear when decisions are being made that hurt our town centers.  Just returned from Savannah Georgia where Leslie and I attended the Congress for the New Urbanism conference. Savannah was founded in 1733 by Brit James Oglethorpe, who is credited for the city's layout and, most notably, its iconic squares. It is a city that not only has a long history, but also boasts a living history book in its one square mile historic district. Savannah's historic district is not only filled with its famous squares, but more importantly, building after historic building offer historical perspective and a sense of place any city would envy. Many of these buildings are accompanied with interpretive plaques to give the passer by details of the building's importance to the city's past. But the buildings themselves add the most value to the Savannah experience. Savannah's buildings span the architectural spectrum from Colonial to Regency to Beaux Arts. These buildings frame the city's 22 squares and give them life and context. Like only a few other cities in North America, their rich form and authentic materials give the visitor the sense that they are on another continent. It is it's preservation of history; not just through tours, signs and plaques, but also through the insistence to preserve irreplaceable buildings, and to maintain their character; that makes Savannah such a compelling place. Savannah is so compelling that 7 million people visit annually. New hotel construction is on the rise, indicative that even more tourists want to experience this magnificent historic district. These new hotels and other new buildings are built with quality materials and with a form respectful of Savannah's pedestrian friendly environment. We spoke to a couple from Northern Michigan who just bought a home in the historic district and plan on spending their winters in Savannah. They said they had been visiting Savannah for years and "fell in love" with it. Savannah's charm and authenticity make it a hard place not to love. Last week, I authored a piece in the Traverse City Record Eagle about the Michigan Municipal League’s assertion that the Great Lakes State’s municipal funding environment is “broken.” Despite 32 quarters of economic growth, Michigan cities, villages, townships and counties across the state are experiencing fiscal stress.

Anthony Minghine of the Michigan Municipal League has made presentations around the state about this problem, recently in my town of Traverse City. Minghine reported that Michigan is the only state in the Union that reduced its per capita funding for local government between 2002 and 2016. All other states had increased their funding, averaging 50%. There are a few key causes of Michigan’s fiscal fall. Michigan municipalities, cities, villages, townships and counties, rely heavily on property tax revenues. Minghine illustrated that Michigan tax code does not track with economic changes. Because of Proposal A passed in 1992, property values, which are free to fall during recessions, are not permitted to rise again at the same pace as the economy when times are good. This makes property values, and the property taxes they are based on, lag behind rising costs and needs. Furthermore, the so-called “Headlee rollback” penalizes municipalities for strong economic growth by reducing millage rates to soften the impact on tax payers. Taxing authorities can restore rates, but only with a vote of the people. Since 1980, Michigan’s population growth has been flat, hovering around 10 million residents. Meanwhile, the state’s infrastructure has doubled. This is largely because of suburban and exurban sprawl. More roads, bridges, sewers, fire stations, fire hydrants, etc. to serve an ever expanding geography of development. The extent of our built world strains Michigan communities’ dwindling resources used to serve it. And because most development in Michigan is sprawl versus urban development, it is low value. Urban development generates far more tax revenue per acre than low density growth. As an example, Joe Minicozzi of Urban 3 conducted a study in 2016 and found that downtown Traverse City generates 83 times the value per acre compared with Grand Traverse County! Some studies show than the cost per acre of urban development is about the same or slightly less than that of other kinds of development. This means that in Grand Traverse County, downtown Traverse City is heavily subsidizing other types of development in the county. Another reason local governments have lost funding ground is related to sales tax. Sales tax is a great way to reward building a strong economy, since tax collections grow as consumers prosper and spend. Unlike in many states where local government can collect sales tax, Michigan only allows the State to collect taxes on sold goods. In return, the State returns a portion of sales tax and other revenues to local governments, based on population, in what is called “revenue sharing.” Unfortunately, Michigan has reduced the portion they give locals as Lansing has struggled over the years to balance its budget. Something’s gotta give, and Michigan will have to fix local government funding. In the mean time, cities, villages, and other local units of government must be proactive and creative in funding their infrastructure and operating costs. Luckily, Michigan offers a number of tools that can help. Grants for downtown enhancements, and programs like brownfield, Main Street, DDA, and Principal Shopping Districts used in conjunction with other grants and private investment can create and support a vibrant business district and town.  The popularity of cities is self evident these days. Millennials and empty nesters are flocking to downtowns across American, attracted by culture, ubiquitous dining options, and the ability to reduce or eliminate their reliance on the automobile. Some cities exhibit so much gravity that high prices and gentrification are real problems. But there is another, related trend of equal importance. This is the growing popularity of so-called “surban” living. The term surban was coined by John Burns, a real estate consultant in California who studies shifting housing preferences. He catalogued an offshoot of the popularity of cities driven largely by millennials who were getting married and having kids. This cohort loves city living, but also looks for the additional room families require, better schools suburbs often offer, and good transit to them to jobs in the city. Burns looked at this trend is the context of larger cities like Chicago or San Francisco, where folks seeking surban living are drawn to walkable suburbs such as Naperville in the Chicago area or Walnut Creek east of San Francisco. These suburbs offer many of the characteristics of downtown, but on a smaller scale, and allow for the house and yard growing families seek. Larger metropolitan areas are well served by surban communities. These larger metros have suburbs with historic downtowns that have the form and density to provide the attributes surban wannabes seek. Smaller city metros, characterized in the census as micropolitan areas, often lack natural surban areas and therefore only have sprawl to offer those not willing or able to live in the central city. These regions have to work harder to encourage development that attracts surbanites. Creating new urban areas (a.k.a. surban areas) requires vision, planning, and leadership. Left to its own devices, development usually comes in the form of suburban sprawl. This is not because there is not market demand for surbia, there is as Mr. Burns found out. Sprawl happens because conventional zoning and transportation policy encourages it, and often outlaws more urban development. Regions must understand their demographics and the housing preferences of their citizenry. Once understood, making sure preferred development is permitted and encouraged is critical to assuring the newly identified need can be met. If your citizens are demanding surban development, you must be sure you have a good plan in place to surbanize! Love watching the Olympics! - especially the winter version. Though USA is not doing as well as expected, its no less fun to watch the games. The Olympics have brought tens of thousands of visitors to Pyeongchang, who are taking in Korean culture and seeing the attractions. Hosting the Olympics brings a great sense of pride to the host community. But does it result in economic gain?

The Olympic debate has been raging for years and is especially interesting because of the high cost of hosting. South Korea is spending around $13 billion, significantly higher than the original $7 billion budget. Ticket sales have been light, perhaps due in part to the recent rancor between North Korea and the U.S. South Korea will not recoup its investment from event revenues and visitor spending during the games, and studies of previous Olympics do not bode well for lasting economic benefit from Pyeongchang 2018. Some cities are grappling with this same question: are large events worth the cost and effort of putting them on? Besides the monetary cost, which sometimes is borne by the city, there are inconveniences caused by increased traffic and limited access to otherwise public spaces. A New York Times Magazine article on the subject noted how traffic was down at the popular Adelphi Theatre in London’s West End and the British Museum in 2012, the same year that city hosted the summer Olympics. Large events, whether they are the once in a lifetime Olympics or World Cup variety, or those that occur annually, can enhance the brand of a community. Besides brand, the same studies that show the dismal economic impact of the Olympics, can’t deny the psychological benefit to the citizens of the cities that host them. It makes them proud of their city, and happier. Large events are like parties, you may not make money on them, but everybody has fun. Downtowns have lives like you and me. Some downtowns are young and growing, others are in the prime of life, firing on all cylinders. Some are like teenagers still figuring out what they want to be when they grow up. Where your downtown is in its life dictates what it needs to get to its next stage of growth.

Young downtowns, like teenagers, need direction and focus. Some teens feel lost and wonder about their place in the world. Downtowns are no different. Some downtowns may have had success, but watched it wane in the face or market changes. Others are new and have never found their way. They need to figure out what their strengths and weaknesses are, and develop a plan for success. Downtowns that are successful can celebrate their prosperity. But no downtown should rest on its laurels. Just like a professional in the prime of her life cannot rely on yesterday’s victories to guarantee more of the same tomorrow. The professional will take stock of her skills and relationships, and work to improve and evolve as the world around her evolves. Great downtowns too must understand that they need to continually transform to remain great. Where is your downtown in its life? Amazon is reviewing 238 proposals from communities to locate a second world headquarters. “Amazon HQ2” will employ up to 50,000 people with an average annual salary of $100,000. One of Amazon’s key requirements for HQ2 is direct access to mass transit. Amazon knows that being in an environment that allows for a carless lifestyle is critical to retaining modern talent. Detroit, which is employing a full-court press for HQ2, is considered hamstrung by its relatively meager transit network. That's ironic, given the recent launch of the Q line street car, which, though a step in the right direction, does little to help the Motor City compete with numerous other cities with rich transit networks offering light rail, bus rapid transit and even subways. Traverse City did not submit a proposal to Amazon. Certainly, the Traverse City area could not check the box on this and other requirements, including a minimum metropolitan population of a million. But Amazon’s recognition of transit’s importance to attracting and retaining high-tech talent should not go unnoticed by Traverse City area leaders. A recent Traverse City Record-Eagle article highlighted the traffic congestion our region is experiencing. The rapid growth of Grand Traverse County has put pressure on its roads. Development that is largely displacing farms and forest continues to force travel origins and destinations farther away from each other. This development is not served by other modes of transportation, so all travel must be done by car, maximizing road pressure. Earlier this year, voters supported a millage for the Bay Area Transportation Authority that included a high-frequency downtown route. This new route, which is being planned and expected to launch in late Spring 2018, is designed to appeal to commuters and visitors. Getting even a small percentage of workers and tourists’ cars off area roads will significantly ease road congestion. Having a viable transit alternative works well with Traverse City’s recent Lyft and Uber service to entice residents to leave their car at home, or even sell a car. But will self-driving cars solve all of our mobility issues? Self-driving, or autonomous, cars will provide yet another option to ease resident’s minds about not driving, but they will not completely replace other modes of transportation, just complement them. In addition to easing road congestion, better transit in our region will position us for the worker of the future. A 2016 University of Michigan study found that 69 percent of 19-year-olds had drivers licenses, down from 90 percent in 1983. Millennials make up the bulk of high tech workers — so their needs are important considerations when discussing strategies to attract them. Traverse City already has a budding tech sector for a town our size. Our quality of life is one attribute that helps attract young workers. Better transit is needed to create an environment where having a car is a choice, not a necessity. We may never be home to a large Amazon headquarters, but with better transit we can become a place where small high tech companies can start up and thrive. |

AuthorRob Bacigalupi helped build one of the premier downtowns in the Midwest Archives

March 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed